An alternate reality

Recently The Guardian published Policy Institute analysis that examined conspiracy theory beliefs amongst the UK public. Among the top conspiracies was the belief that 15 minute city plans are an attempt by government to surveil people and restrict their freedoms. Quite unbelievably, a third of respondents felt that this was either definitely or probably true. It seems that the way we design our cities is finally reaching a level of national consciousness. Unfortunately, it is doing so for all the wrong reasons!

To pedal back a little, anyone likely to be reading this blog is also likely to be familiar with the concept of 15 minute cities or the closely related notion of 20 minute neighbourhoods. Both argue for shaping urban environments in order to allow people to live lives that are supported by all necessary facilities and amenities within a walkable or cyclable distance of their homes. For such an entirely reasonable and one would think uncontentious idea to be caught up in the alternate realities of the conspiracy theorists is difficult to comprehend.

This, the Policy Institute inform us, is a consequence of the manner in which we all now consume our news. Notably, an increasing number of us are choosing no longer to engage with media outlets that, to varying degrees, attempt to air alternative viewpoints, in favour of those that only seek to represent narrow worldviews. Taking that path, one can all too easily disappear down a rabbit hole of interlinked conspiracy theories where even the most innocuous of policy approaches is seen as a sinister plot against personal freedoms. That, it seems, is where we have got to with 15 minute cities.

The idea of responsive neighbourhoods

In this post-truth world, the idea of 15 minute cities somehow became embroiled in the UK in controversies over the introduction of low traffic neighbourhoods (LTN). These attempts to reduce street space and inter-connectivity for drivers in favour of pedestrians and cyclists have been seen by some as a direct attack on what they see as an inalienable right to drive wherever and whenever they wish. Others have come to believe, quite literately, that the intention is no less that to pen populations into their neighbourhoods and not to let them out!

Such mentalities may very well reflect a hangover from the covid lockdowns that, to varying degrees around the world, imposed such restrictions on us. More likely, LTNs and 15 minute cities simply became conflated as both ideas rapidly gained traction in a post-pandemic world in which many of us have been opting to spend more time in our home neighbourhoods and rightly have come to expect more from them.

As an idea, 15 minute cities and 20 minute neighbourhoods are nothing new, but are instead a re-branding designed to catch the attention of politicians; which they have done in spades. Perhaps the best known example is Paris, home of the originator of the term 15 minute city – Carlos Moreno – and where Mayor Anne Hildago made the concept a centre-piece of her successful 2020 re-election campaign. This was clever politics, according to some, as Paris is ostensibly already a 15 minute city, making delivery of this election promise very easy to deliver. And anyone who knows Paris, also knows that this particular 15 minute utopia is hardly a dystopia of surveillance and control as the conspiracy theorists would have us believe.

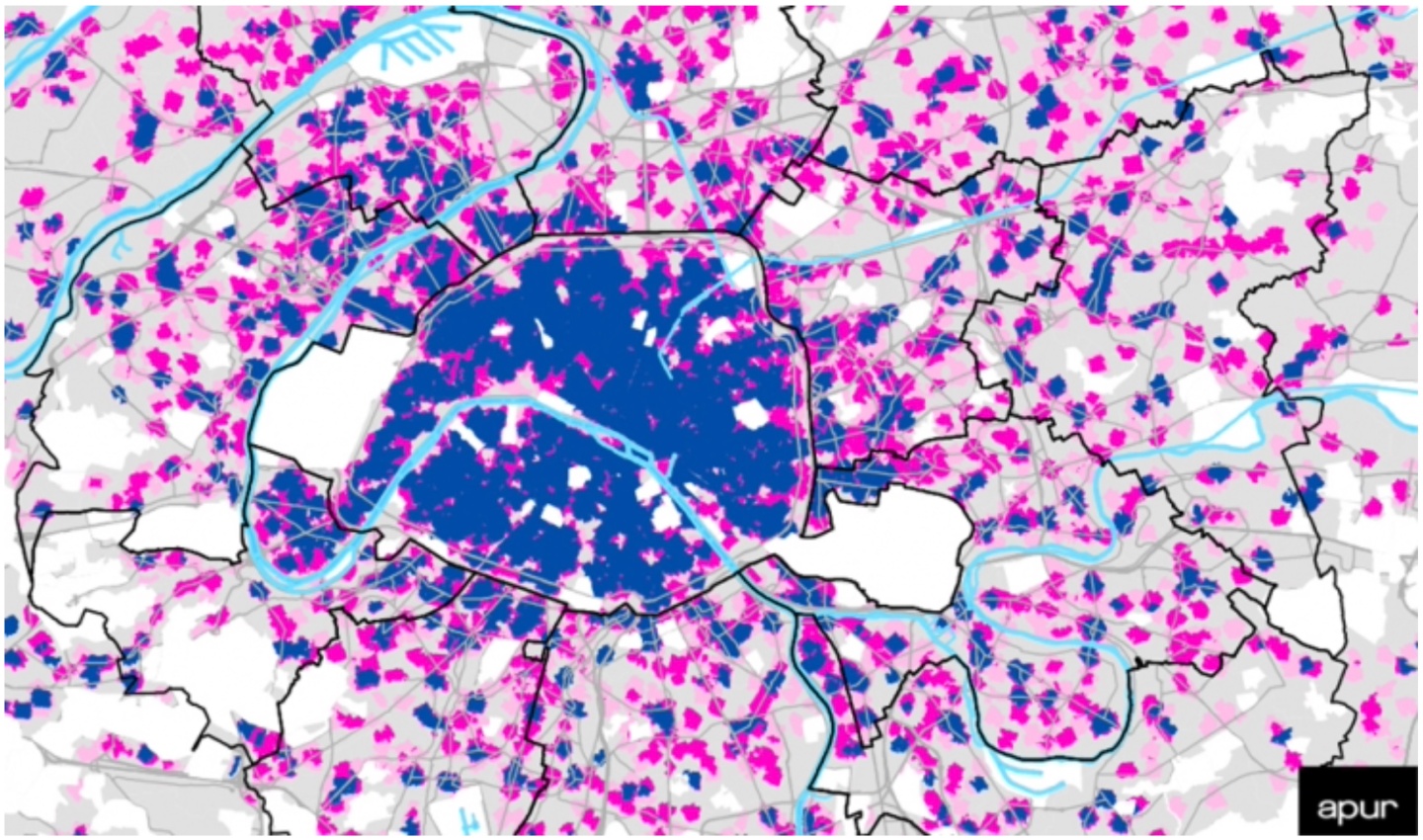

Key: blue, all three reachable in five minutes; dark pink, two of the three reachable; light pink, one of the three; grey, areas where residents (4% of the population) need to walk further than five minutes to reach at least one of the three

While many traditional cities, just like Paris, have tended to grow organically on a neighbourhood model, the idea of deliberately designing localities in which there is good convenient access to meet all daily needs goes back to the origins of neighbourhoods as a planning idea. Famously, this included Clarence Perry’s influential work a century ago on ‘neighbourhood units’, which, just like the 20 minute neighbourhoods of today, contained certain critical elements: an elementary school, open and play space provision, local stores, and a configuration of building and streets that allowed all public facilities to be reached safely on foot.

Even more famously, campaigning in the 1960s to preserve her equivalent of the 15 minute city – the mixed city – Jane Jacobs opened the worlds eyes to the critical social bonds that liveable localities can support. Her fight for traditional neighbourhoods and against the imposition of top-down Big Government programmes to re-shape cities in favour of the car, was the polar opposite of what the conspiracy theorists argue today. For them, the hand of Big Government is seen in attempts to preserve the integrity of the small and the local by taming the car and seeking to transform neighbourhoods into liveable places. But instead of making their case through evidence and reasoned argument (Jacobs-style), these new advocates reach for wild speculation and unsubstantiated rumour to make theirs.

Time as a surrogate for density

Underpinning the 15 minute city concept (or brand) is the use of ‘time’ as a simple surrogate for a whole series of factors that make for a good city. These include: density, diversity, mix, and connection; all long-held shibboleths of the urban design cannon since the days of Jacobs. But taken literally, time travelled can be quite a crude measure of place quality.

Scotland, for example, is in the final stages of introducing Planning Guidance focussed on Local Living and 20 Minute Neighbourhoods. As the name suggests, this takes 20 minutes from the home as the measure “to meet the majority of daily needs”, “by walking, wheeling or cycling” (wheeling meaning by wheelchair or mobility aid). However, where you can get to in 20 minutes on foot compared to 20 minutes on a bike is very different. The average pedestrian will walk around 3-4 miles per hour (say 1 mile in 20 minutes), mobility aids may be slower or faster depending on how propelled, while cyclists will travel about 12.5 miles per hour (say four miles in twenty minutes). But as many people cannot or choose not to cycle for all sorts of reasons (particularly women), a twenty minute travel distance for one person on a bike will be a one hour twenty minute journey for someone walking, making the measure less than useful.

The great benefit of living in an urban areas is that they provide all the amenities we need, reflecting the fact that what will be a critical daily need for one person, such as a hospital visit, may not be for someone else. The trade-off is that these needs will be met at different distances from our homes. The corollary of this is that while we absolutely need to focus on the local, it is not the be-all-and-end-all (as a 15 minute city may unintentionally imply). We also need to focus on those vital intermediate and longer distance needs that the good city should meet.

Also, when we consider the local, rather than starting at 15 or 20 minutes, we should begin at 5 minutes from the home. Home Comforts, the Place Alliance study undertaken during the first UK lockdown showed that people quickly became more dissatisfied with their neighbourhoods after a five minute walk distance had been breached. Thinking in this way, we might need access to parks and local shops within a five minute walk; primary schools, good public transport provision, personal services such as haircutting, a pub or café, and local health services, within 10 minutes; larger town centres, emergency medicine, social facilities, and a diversity of work opportunities within 20 minutes; and access to more specialist hospitals, universities, public administrations, and so forth, within 30 minutes (this final category traversed by any mode of sustainable travel).

Ultimately, what this all really comes down to is density. Indeed, Carlos Moreno always heavily caveats his many presentations of the 15 minute city concept with the need re-shape cities around ideas of poly-centricity, proximity and diversity.

Paris, for example, has an average density of 86 persons per hectare explaining how much of it (as already illustrated) is a five minute let alone a 15 minute city. London is less dense, but still has an average density of 69 persons per hectare, while across the UK the average urban density is 37 persons per hectare. The implications of this is that in most UK towns and cities, people will need to walk roughly twice the distance that Londoner’s do to get to the sorts of amenities that are dependent on having a large enough population to justify them, such as shops or a GP surgery. Outside of London, new suburban expansions are often built at considerably lower densities than even this, explaining why, in many cases, residents in such areas choose not to walk, and instead (if they have one) take the car. At 37 persons per hectare, assuming around 2000 people are required to support a corner shop, 54 hectares of land would be required to house the population for a single shop. At such densities, most facilities (including public transport) would most likely exceed a 15 minute walk.

Time for a re-brand?

Unfortunately, even the most innocuous brands can quickly become toxic if enough disinformation is thrown their way. Despite its shortcomings, it will be a great shame if that happens to the 15 minute cities idea given the ability of this “mundane planning theory” (as Oliver Wainright described it) to cut through to policy makers, around the world. In England, we have had many initiatives to try and containing sprawl and building more densely, including, in recent decades: urban villages, millennium communities, urban renaissance, sustainable communities, eco towns, garden communities, and gentle density. So, if that occurs, no doubt another similar brand will come along soon.

The new Scottish Planning Guidance anyway notes that we need to be realistic that remote rural locations may not be able to achieve the aspiration for residents to meet the majority of their daily needs within a 20 minute walk. In fact, without dramatic changes to their structure and density profiles, many suburban locations, including many of the UK’s suburban expansions of the last 30 years, also fall into this category. The challenge, therefore, is a more fundamental one than making provision for a few additional local facilities where they do not exist. Instead, where it is both possible and desirable (which isn’t everywhere), it is about connecting-up, retrofitting and densifying existing places. This is a much more wicked problem, and one (like LTNs) that is unlikely to have universal support! Perhaps we need a sexy brand to sell it, I know, how about 16 minute cities?

Joking aside, as a starting point, ensuring that newly built neighbourhoods are built at sufficient densities to support day-to-day needs locally, while connecting into wider sustainable transport provision for longer distance requirements, must be a first step to creating decent, well-provisioned, healthy neighbourhoods for all. Elsewhere, a strategy of gradual densification by stealth has much to recommend it: investing in public transport, densifying around nodes of activity, proactively bringing forward small development sites, building adaptably to allow changes of use at ground floor level, and gradually reducing parking, while all the time hoping that those conspiracy theorists don’t notice!

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL