Design in planning

I have written elsewhere about how places are shaped (for good or ill) by multiple overlapping processes through time. This involves inputs of different actors working both together and sometimes seemingly in opposition to each other. Broadly, five professions play key roles in shaping the built environment: planners, real estate professionals, engineers, architects, and landscape architects. Yet only the last two are typically regarded as ‘designers’.

This distinction is reflected in academia. Planning and real estate are typically seen as social science disciplines, engineering as a science, and architecture and landscape architecture as design disciplines. Of course, reality is more complex. Engineers, for example, don’t just do calculations, they also design projects, and architects don’t just design, they are also concerned with the science of buildings. But these disciplinary boundaries shape who teaches what and how and in which type of faculty – often leading to planning being taught as an analytical, policy-based subject rather than a propositional one. Given this, it is unsurprising that over the decades planning has drifted away from design.

So where does that leave urban design, and why didn’t I list it among the five? Two reasons.

First, urban design sits across all the built environment disciplines but is usually viewed as a specialism pursued after an initial professional qualification. Many of us believe this is the wrong way around, and that all built environment professionals should begin by studying urbanism as a shared foundation, before specialising later. As in medicine, we should learn the ‘whole body’ before becoming specialists in its parts. But the grip of established professions remains strong, and an ‘urban sensibility’ often gets lost.

Second, as I tell my students – many of whom take just a single urban design module – “from this day on, you are all urban designers”. Whether preparing a spatial plan, advising developers or a community, or assessing a development proposal, planners shape real places. That is urban design. Planning is, therefore, a design discipline, and if planners are to do this consequential work well, design thinking must be part of their education.

Early planners understood this. In 1911 in his book Town Planning in Practice, Raymond Unwin wrote that too much planning “lacked the insight of imagination and the generosity of treatment which would have constituted the work well done; and it is from this well-doing that beauty springs”. Unwin – an architect / planner – was not making an aesthetic argument. He was calling for aspiration, creativity, and humanity in planning: qualities distinct from the analytical or technical mindset that science brings. If that sensibility was rare in Unwin’s time, the complexity of contemporary planning makes it even harder to sustain – although not impossible.

A good example can be found in Stockton-on-Tees. In the late 2010s, as retail decline hollowed out the high street, the council took a bold step. It bought the failing Castlegate Shopping Centre and Swallow Hotel, asked residents what they wanted, and – with overwhelming support – decided to demolish them. In their place, it planned a new urban park, opening the high street to the River Tees and creating a more compact, viable retail core.

This vision required imagination. The market had failed and analysis could diagnose the problem, but only a design sensibility could see a different future. That is planning as the ‘art of the possible’, where creativity and pragmatism combine with a long-term vision to make real change.

We can capture this sort of planning in five assertions:

- Planning is spatial and manifests as physical change. To grasp its potential, planning must embrace design.

- Planners must be creative thinkers, not necessarily designing projects themselves, but imagining new possibilities in a questioning, problem-solving manner.

- Design cuts-through to ‘non-design’ professionals and communities because it is tangible and propositional, unlike abstract policy and obtuse regulation.

- Planners must articulate a clear vision, by approaching urban problems and advocating solutions proactively, not just administering the bureaucracy of urban change

- All change (not just heroic interventions) matter. From major projects to everyday interventions, each cumulatively affects the public realm and society and should be seen as opportunities for improvement.

Planning to design

Ultimately, if urban planning is to be seen as a positive force for change, and not simply as a reactive regulatory hurdle, then planners need to be trained to be problem-solvers and solution-oriented proactive thinkers, much in the same way that architects are. That requires teaching design thinking – or what Nigel Cross called ‘designerly ways of knowing’.

But most planning courses are short and theory heavy. In the UK, many are just one year long with little or no design content. In contrast, architects and landscape architects spend five years developing design and communication skills. The result is that design is often treated as a niche within planning, isolated in schools dominated by social science thinking and analysis.

The Royal Town Planning Institute’s own ‘learning outcomes’ for accredited programmes illustrate the problem. Of the 14, only one relates to design, and it merely requires students to ‘evaluate’ design principles, not ‘practice’ them. Extraordinarily, there is no requirement for planners to actually plan, let alone design. The 13 ‘quality recognition’ criteria used by the Association of European Schools of Planning almost entirely ignore design and even plan making, only referencing design in passing as a possible specialist area.

Perhaps this is a pragmatic response to the lack of time to teach design properly. But that seems to admit defeat before we have even begun, consigning planning to a marginal regulative activity, rather than – as its name suggests – a profession with something to say through its fundamental purpose, to plan ahead.

At UCL’s Bartlett School of Planning, we try to challenge this orthodoxy. Across our programmes, design is embedded to varying degrees – sometimes as the core focus, sometimes as specialist stream, and sometimes as a single urban design module alongside a second that focused on spatial planning at a larger scale.

Our MSc Urban Design & City Planning (UDCP) and BSc Urban Planning, Design & Management (UPDM) go furthest. UDCP students take six of eight modules on design practice and theory and finish with a design-based research project. UPDM students develop design skills progressively over three years alongside studies in planning and real estate.

These programmes don’t aim to produce ‘masterplanners’ ready-made, but rather forward thinking, proactive and creative planners, able to tackle the most complex urban planning problems with flexibility and flair, whether through policy, guidance, regulation, plan-making, negotiation, engagement, coordination, or proposition-based advocacy. If they wish to move into urban project design, these programmes offer a point of embarkation rather than a final destination.

Exceptions are MSc UDCP students who are already architects or landscape architects when they join us. These students (about 50% of those who join the programme) are able to further refine their project design skills at an urban level, while also picking up the larger urban design and spatial planning skills that will refine their practice.

Ultimately, whatever the background and experience of students, and whether destined to be project designers or creative planners, I would advocate seven key steps to teach design to planners:

1. Expose students to creative thinking, I contend that we are all inherently creative thinkers and problem-solvers, as evident in the imaginative play of children. Unfortunately, the obsession with passing exams often ‘teaches out’ these innate human traits. As I have already argued, the ability to envisage the art of the possible is fundamental to shaping successful places. Therefore, the first step in educating planners should be to set ‘wicked’ problems that can only be addressed through creative, design-oriented thinking. It is this mindset that distinguishes the best students and will continue to do so, even in a world increasingly dominated by AI.

2. Use hands-on and project-based learning, This kind of learning cannot be achieved through essays, exams, or data analysis alone. Students must engage directly with real places and problems, primarily through site-based projects. Such projects take time to design and are complex to manage, but no amount of reading or writing can substitute for the experience of first understanding real places and then imagining how to transform them for the better.

3. Encourage learning through repetition, Architecture education benefits from the luxury of time, allowing students to refine their design skills through progressively complex, long-term projects. Planning and urban design education rarely enjoys that same luxury, but a similar process can be replicated more intensively through a greater number of smaller projects. At UCL, for example, students on the MSc UDCP complete three projects each term (each with multiple components) and these culminate in a longer, supervised Major Research Project over the summer.

4. Value interdisciplinary group work, In the real world, complex urban problems are rarely solved by individuals working in isolation; they are addressed by interdisciplinary teams. Replicating this in education presents challenges – such as grading individuals fairly and recognising the different skills and knowledge students bring – but the benefits are substantial. Discussing problems from diverse perspectives enriches the learning process. Group work, and where possible interdisciplinarity, should therefore form the foundation of any urban design programme.

5. Use theory selectively to open up minds, Academics love to theorise, but planning educators should always ask:‘How does this help students find solutions?’ Most students enjoy engaging with complex urban ideas and debates, but they are rarely inspired by overly abstract theorists such as Lefebvre, Deleuze, Foucault or Agamben. Understandably, they are more concerned with employability, and employers seek doers, not theorists. Theory should therefore serve as a means to broaden horizons and open minds, suggesting ways forward rather than merely signposting more problems.

6. Avoid designing by numbers, Just as excessive theory can obscure rather than clarify urban issues, overly rigid step-by-step design methodologies can stifle creativity. Much of the learning lies in defining the process itself, not just in the solutions it yields. Academics should therefore provide only a loose framework to guide students’ work, focusing instead on stimulating ideas and feeding in material for reflection. Striking the right balance is crucial, especially in international classrooms where students may come from traditions that emphasise replication of ‘the master’ rather than active questioning.

7. Focus on the ‘big picture’, Students often fixate on details – “Does it look right?”, “How can I express that graphically?”, “Is it viable?” – but the best creative planning practices are as much about recognising and shaping opportunities and decision-making contexts as about detailed design, which can be left to others. Consequently, I encourage projects that are strategic in nature, operating at the scale of the whole place rather than individual buildings or spaces, often emphasising tools of design governance over masterplanning. This approach is accessible to those new to design who need not grapple with detailed design, and illuminating for experienced designers, who benefit from retrofitting their detailed knowledge with an understanding of the urban scale.

Reclaiming the name

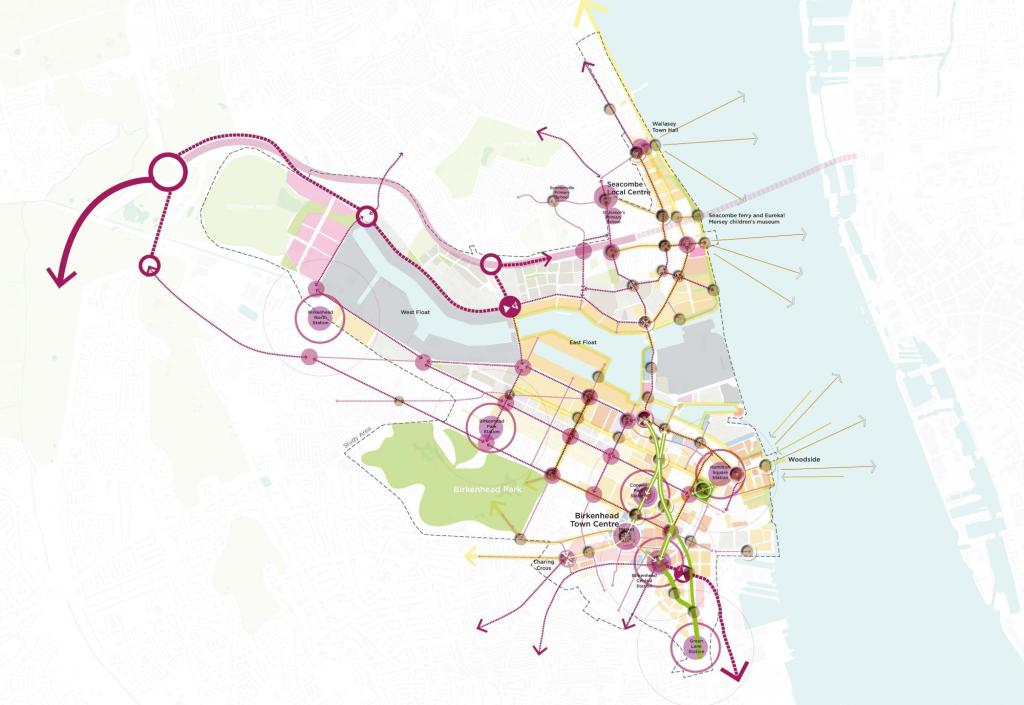

Planning is, and always has been, a design discipline, even if it has forgotten it. The three figures in this blog represent the design scales across which the design dimension of planning needs to apply: from the multiple project scale represented by the Birkenhead 2040 Framework; to the level of the individual urban project illustrated in Stockton-on-Tees; to the quality of the public realm as represented by London’s artist-designed zebra crossings.

To rediscover its purpose, planning education must once again teach students how to imagine, shape, and advocate for change across these scales, and not just analyse it. Only then will planning truly earn its name.

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL