This summer, a Visiting Professorship to Diponegoro University in Semarang, coincided with the publication of the first part of a new two part paper examining Urban Design Leadership. The conceptual framework provided by the latter offered a useful lens through which to reflect on the former.

Coordinating and integrating

In any design-based discipline, the emphasis is often on the creative act of design and what that delivers, but the act of design sits at the centre of a place-shaping process which needs to be ‘mastered’ (aka led) in a manner that directs efforts towards achieving positive outcomes, namely high-quality urbanism.

Yet given that any built environment intervention will follow a leadership process to deliver a set of outcomes, the question arises, what distinguishes urban design leadership from leadership associated with, for example, architecture, landscape or infrastructure design. Urban design has been defined in many ways – relating to the scale across which it operates, in relation to other professions, in terms of the knowledge fields from which it draws, or, most often, as a set of normative principles. Most of these substantially overlap with and can also be used to define the allied disciplines that surround urban design.

Looked at another way, it is exactly this overlap that sits at the heart of what should distinguish leadership in urban design relating to the essential integrative and coordinating nature of the discipline. Indeed, as a range of writers imply, if urban design does not focus on integrating, it is not urban design at all but instead a simpler form of artifact or project design such as a bench, a building, or a bridge.

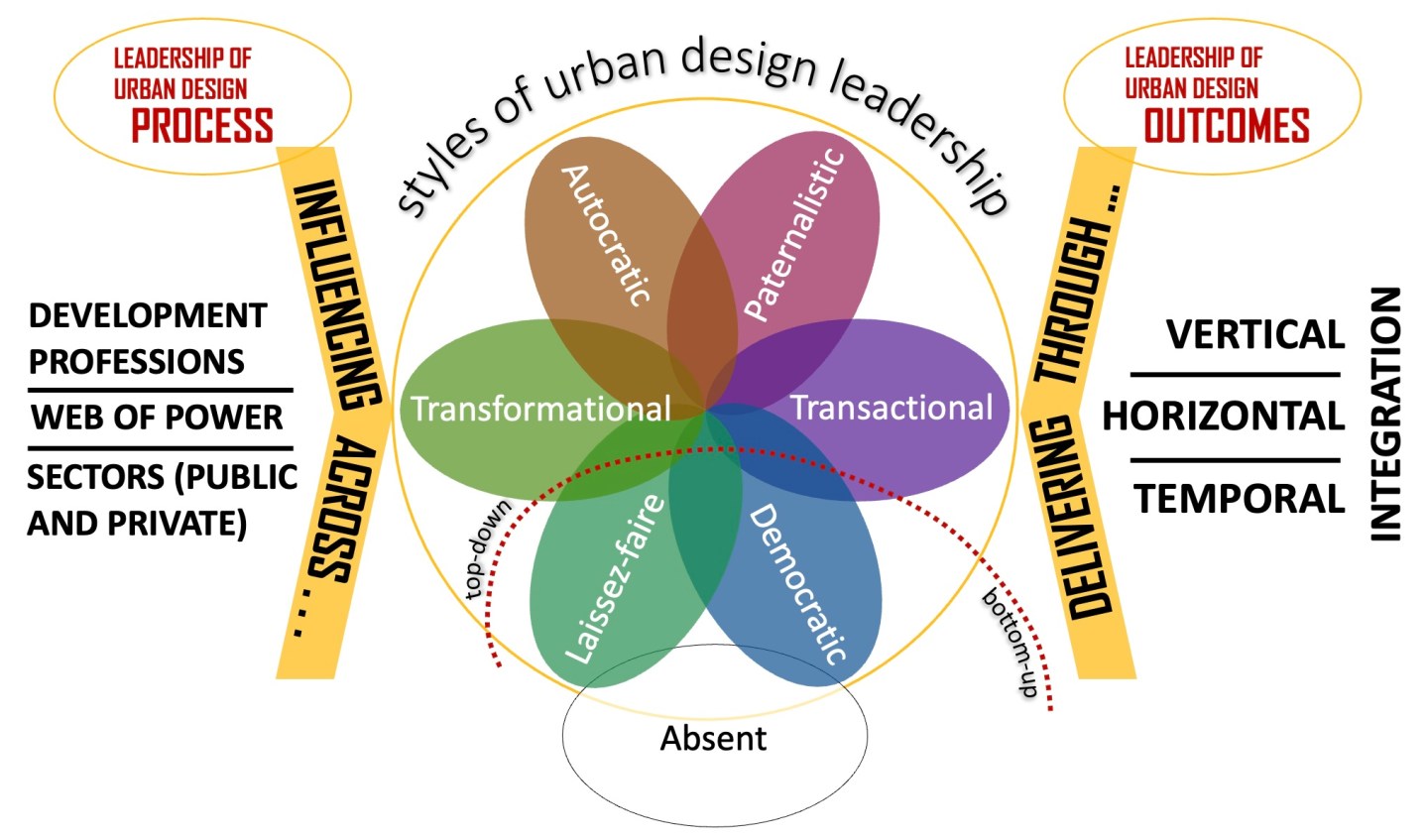

For this reason, the initial conceptualisation of urban design leadership in the paper was framed through its fundamental joining-up function which sets it apart from other built environment disciplines and relates to both processes (1-3 below) and outcomes (4-6):

- Leading across the development professions – joining-up a fragmented and often estranged set of remits through connecting fabric and processes

- Leading across sectors (public / private) – in a field where absolute leadership is rare and represents a negotiation across the public/private divide

- Leading across the web of power – utilising creative visioning to conceptualise viable urban propositions and reconcile sometimes contrasting aspirations.

- Leading through vertical integration – across the range of spatial scales, with different objectives, tools, and dynamics at each spatial scale

- Leading through horizontal integration – emphasising the importance of continuity, connection and synergy between individual urban developments

- Leading through temporal integration – accepting that places are shaped through time as part of an ongoing continuum of change that is unknown

Styles of urban design leadership

Turning to the form leadership takes in urban design, six substantive styles and a seventh – its absence – are identified and fully explained in the paper, the most critical characteristic being whether they are top-down or bottom-up. None of the leadership styles (or characteristics) are absolute. Instead, they overlap and present themselves in different ways in different places at different times. That was certainly what I observed in Indonesia.

Today Indonesia is defined as a middle income country of the Global south, with a large rapidly growing economy, a stable democracy, and a young population. This has manifested itself in high population growth and strong rural/urban migration, particularly on the Island of Java where over half the county’s population is located, including the capital city Jakarta (approaching 11 million) and eight other cities (including Semarang) with a population of between one and three million. These cities combine a rich and vibrant culture with problems brought on by congestion, a lack of basic services and housing, and (in places) a deteriorating environment, all of which has dampened the prosperity gains from urbanisation.

All the forms of urban design leadership can be recognised in Indonesia’s cities:

1. Autocratic

Autocratic leadership in urban design is often the consequence of an autocratic leader taking top-down decisions about what should be where and how and might be seen as an anathema to democratic ideals. However, there are circumstances in which even representative democracies come close, notably in relation to the grand tradition of building capital cities. This was not a type of development I witnessed first-hand in Indonesia, but it did loom large in discussions in relation to the design and planning of Indonesia’s new capital city – Nusantara – on the island of Borneo. This top-down project to establish a new seat of government and home for 2 million people was instigated in 2019 at the direction of the then president and in the teeth of opposition from indigenous peoples being displaced and concerns about the impact on local wildlife. It required a constitutional amendment to ensure its delivery which is managed by the Nusantara Capital City Authority accountable directly to the President. The masterplan is based on an international design competition which defined Nusantara as ‘Indonesia’s smart and sustainable forest city’, although early phases suggests more Haussmann than holism.

2. Paternalistic

Paternalistic leadership in urban design reflects a traditional top-down approach where elected governmental organisations at different levels in the hierarchy (national to local) enact policies and propositions from the top-down in a manner that they perceive to be in the best interests of their populations. But rather than basing them on engagement with populations (beyond the democratic process), they are instead largely based on professional and political conviction. A clear example is Semarang’s old town, Kota Lama, which has been undergoing a regeneration, initially spurred by heritage loving local entrepreneurs, and latterly by the city government which has been promoting its colonial heritage as a candidate for the UNESCO world heritage list. This has involved scrubbing and ‘restoring’ the area to reveal something of its former glory, although not, unfortunately, always with a full possession of what is or isn’t authentic. Recently, for example, this has included demolishing key buildings for car parking and installing public realm features more reminiscent of Paris (again) than the former Dutch East Indies. The result seems rather sanitised when compared to the vibrant hustle and bustle typical of so many Indonesian neighbourhoods.

3. Democratic

Modes of democratic decision-making might vary along a spectrum from decisions simply being made by elected representatives to community led processes. In the business management literature, democratic leaders focus on building a rapport so that decisions are based on a consensus that takes advantage of different skills and perspectives. Translating this to urban design, a democratic leadership approach would imply broadening out decision-making to include a wider range of stakeholders and organisations representing different development interests, and importantly, the community. I witnessed this in Tambak Lorok, a fishing village that is gradually sinking into the Java Sea, yet the community support each other to collectively plan for the settlement’s future, including trying to raise incomes through building their own fish market within the village to sell products directly to their customers. Local democracy acting through the Village Head ensures that the village is represented at higher governmental tiers and has been able to successfully capture and utilise resources to raise street levels, provide communal facilities such as public toilets, and create spaces for the community to meet and interact.

4. Laissez-faire

Laissez-faire leadership implies a hands-off approach whereby public sector leaders largely eschew taking on a leadership role in relation to design quality and instead look to the market to define and deliver a vision. This model is common throughout the world, but in the Global south where public resources are limited, it can dominate large scale formal (as opposed to informal) urbanisation practices, with private corporations often given free rein. Naturally the market chooses to build what gives the best return and that is often exclusive gated communities that cut off wealthy residents from society at large (and all of its ills) behind high walls and security. In Jakarta, the Pantai Indah Kapuk (PIK) represents a case-in-point. Developed by some of Indonesia’s largest real estate developers, it takes the form of a sequence of private gated enclaves around a sprawling roads based infrastructure and sequence of private exclusive malls and leisure facilities. According to some, PIK has been developed with scant regard to regulations or its impact on the neighbouring mangroves and communities.

5. Transactional

Transactional leadership implies that leader–follower relationships are defined as a transaction. While this may characterise almost any relationship where a consultant is hired to deliver a service, some forms of urbanism and the processes that create them are notoriously formulaic, being driven by consultancies who sell similar products across nations and internationally. The urban extensions being planned around Semarang fit into this category, including Bukit Semarang Baru (BSB) City in Semarang’s south-eastern hills or the Pearl of Java (POJ) City on its north-eastern waterfront. The former is designed by the Japan based international consultancy, Nikken Sekkei, and the latter by Singapore based international consultancy, ENCITY. Both ‘products’ mix seemingly attractive environmental visions (respectively, a ‘green city’ and the ‘first seaside ecotourism destination’) with a programme of selling sprawling suburbia and the other amenities on offer. This transactional emphasis even extends to charging for entry to key amenities on offer, such as playgrounds and parks.

6. Transformational

Urban design leadership that is transformational is often associated with inspirational leaders who are able to motivate and inspire followers to deliver positive change based on their ideas, passion, and force of argument. Equally, transformational leadership in urban design may simply involve municipalities delivering or facilitating interventions that are themselves transformational in their impact, setting a new higher benchmark for others to aspire to. The Tebet Eco Park in Jakarta is such an example, designed by SIURA Studio and delivered by the DKI Jakarta Provincial Government, the project revitalised a previously aging public park with a degraded environment, difficult accessibility, flooding problems (from an open sewer), and an association with antisocial behaviour. From this, a new heart for the surrounding communities has been forged, in which ecological diversity mixes with an inclusive human environment full of diverse recreational possibilities that have been attracting investment to the surrounding streets.

7. Absent

A final type is the complete absence of leadership, or at least absence in a formal capacity. Common in Indonesia, like many rapidly urbanising contexts with a still immature local governance framework, are illegal and unregulated developments of different types. At its worst (and most ubiquitous) are the sorts of informal urbanisms – slums – built by and occupied by the poorest communities. These kampungs (as they are known locally) typically spring up in unwanted and degraded areas of cities, next to railways, major highways, drainage channels, areas of flood risk, and the like, where they are populated by the poorest populations. While lacking access to even the most basic amenities and liveability, they are not without design qualities but instead respect a self-organising code dictated by their construction, materials and social and cultural rules giving them a sense of logic and chaotic order.

A framework for analysis

The framework presented in this blog suggests that leadership in urban design manifests itself in multiple and frequently dramatically different ways, often (as the Indonesian example suggests) in the same geographic locations. While recognisable as broad ‘types’ or styes of leadership, these are rarely the same from place to place, but further divide by how they respond to different professional, sectorial, and power structures; and how they integrate practices vertically, horizontally, and temporally.

Ultimately, they will be determined by those with an interest in design outcomes being able to lead. In other words, by how the governance and development structure gives agency (or not) to those with an interest in shaping better places for people than would otherwise be produced. I will explore this in the next blog. Rarely will this be an individual task, but more often a shared one in which much leadership in urban design remains hidden from public view.

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL

Acknowledgement: profound thanks are due to colleagues at Diponegoro University’s Department of Urban and Regional Planning for their knowledge and the kindness they showed during my recent visit, and in particular to Dr Wakhidah Kurniawati for organising the trip.