Financial mechanisms and urban design governance tools

Urban design aspirations do not exist in a bubble. The most creative design solutions will be of little value if economic systems fail to allow for their implementation. Urban design outcomes and processes will always be shaped by the availability of economic resources and the nature of financing instruments for projects. But the governance of design has the potential to use financial (and other economic) means alongside or as part of the urban design governance toolbox to incentivise good design and discourage poor design.

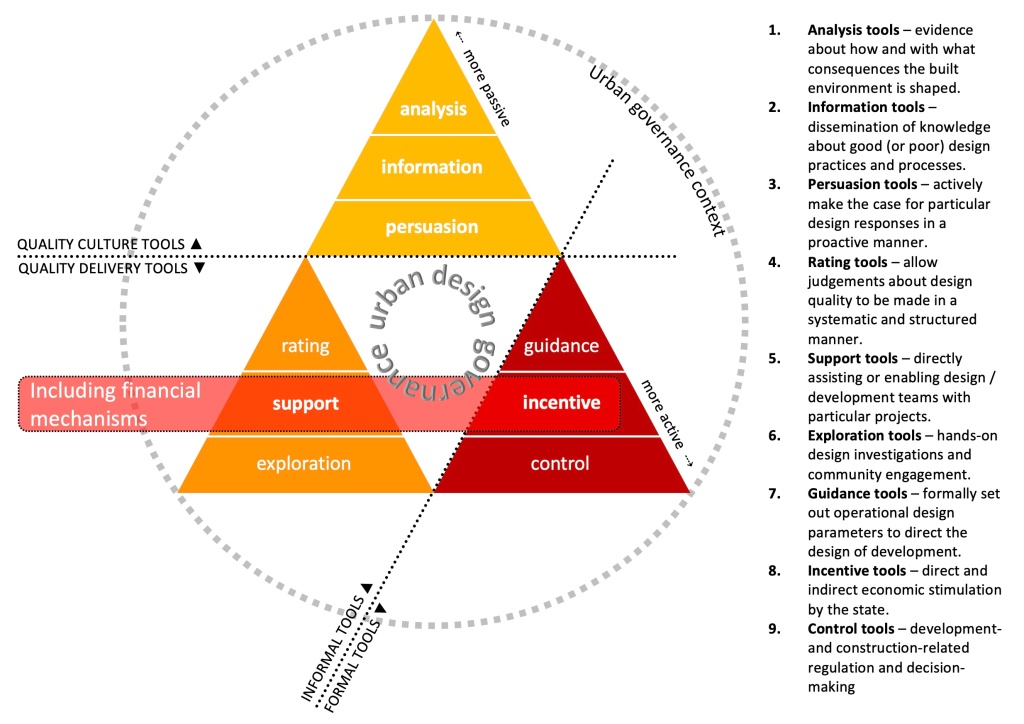

The Urban Maestro project examined the use of urban design governance tools across Europe, summing up the types in a nine-part typology. One strand of the project – recently published in a new journal article – focussed on how the tools of urban design governance interface with financial mechanisms. Looking across Europe, the research revealed that at a basic level, financial means can encourage the production and use of particular urban design governance tools through the allocation of support funding for such activities. More significantly, however, finance can be used to encourage the delivery of public design aspirations as captured in the formal and informal tools of urban design governance. Used in this manner, finance is a formal incentivisation mechanism.

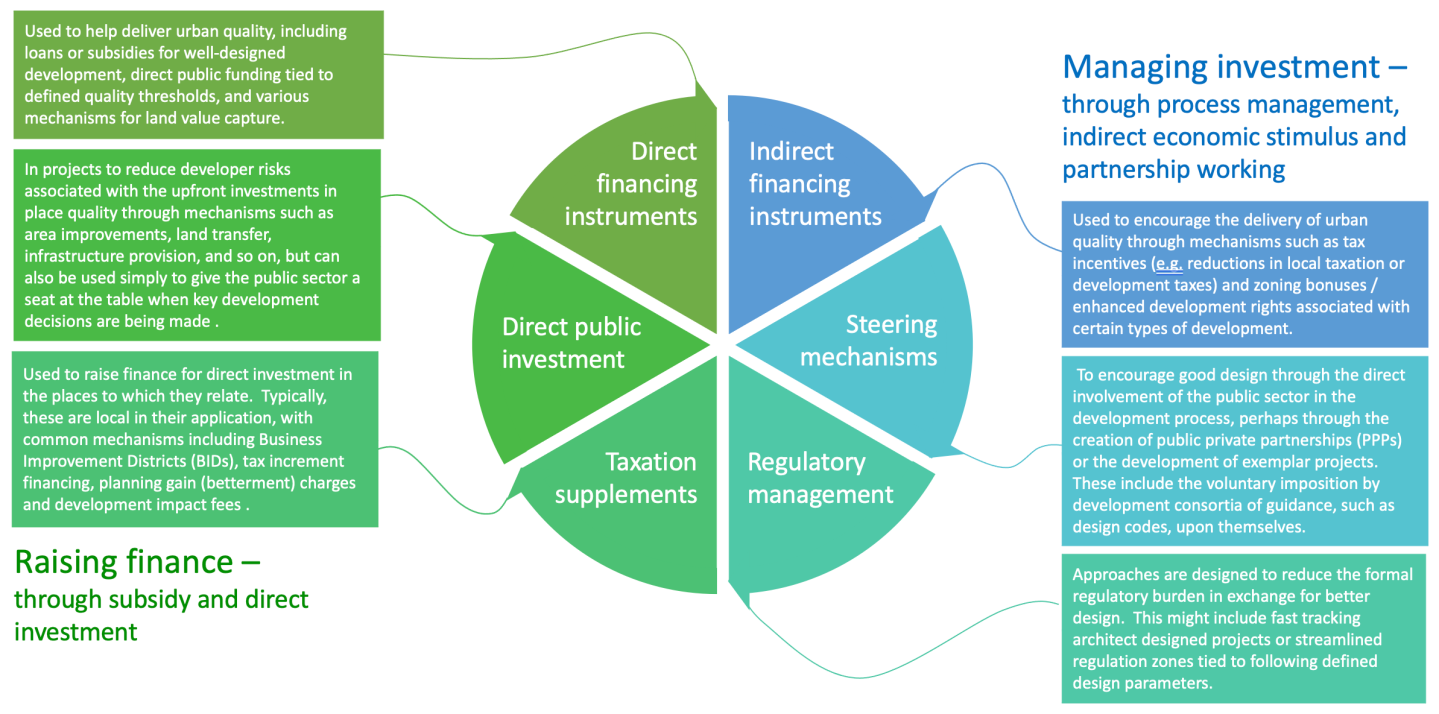

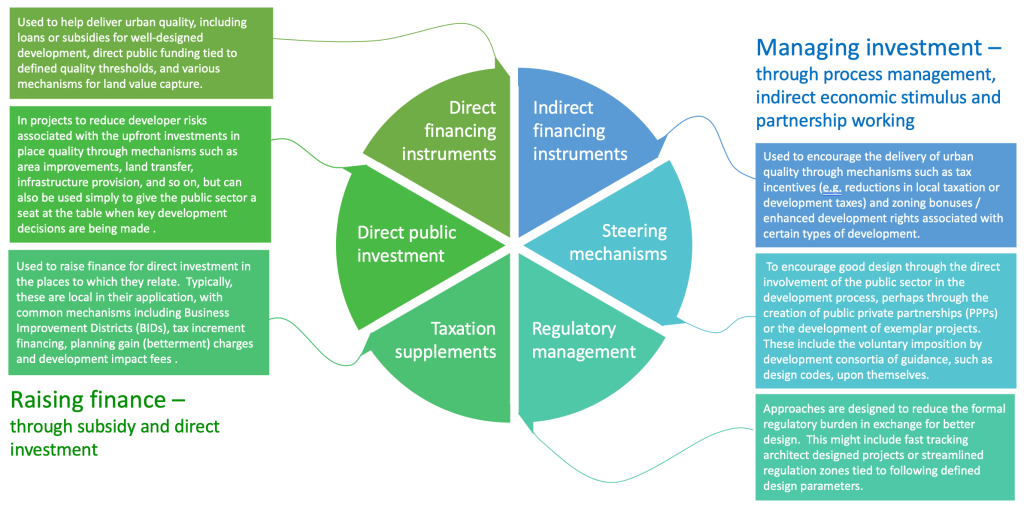

While any financial mechanism might, in theory, be used for that purpose, in practice some are far more commonly used than others. These can be classified across two meta-categories encompassing, first, the ‘Raising of finance’ through subsidy and direct investment and, second, ‘Managing investment’, variously involving process management, indirect economic stimulus and partnership working.

A design / finance gap

A Europe-wide survey of state-level government administrations as part of the Urban Maestro project suggested that while all the financial mechanisms included in the classification are used across Europe, awareness of the potential to link between financial approaches and design tools was low, suggesting in turn that the association remains underexploited. For example, follow-up in-depth research revealed that few built environment professionals could fully unpack the economic rationale and business models associated with specific urban design governance tools.

If the critical task for the state is not simply to incentivise development, but to incentivise high quality development, the research suggested that currently many administrations are attempting to do this without critical financial tools (or even understanding) at their disposal.

An obvious conclusion was that European urbanists need better training as their understanding of real estate dynamics is often poor and without such an understanding it is difficult to engage real estate interests by bringing ‘asset values’ as well as ‘potential values’ to fully bear on positively shaping places. The reverse is also true, that real estate actors – including those working in the public sector – need better means of accounting for ‘place value’ and not just economic value.

But not everywhere …

Despite the gap in practices and awareness, the Urban Maestro project found numerous examples of design quality tools working directly with financial mechanisms to drive up quality thresholds, many of which are described in the project’s website, and brought together in the article that underpins this blog. Four cases demonstrate the variety of these practices, the first two from the ‘raising finance’ and the second two from the ‘managing investment’ meta-categories.

- The Stadmakers Fonds (Citymaker-Fund) was created to address the difficulties that non-conventional place-making projects encounter with securing finance from traditional sources. The fund acts as a matchmaker between place-makers and investors with an emphasis on projects that contribute to delivering a clear social as well as economic return. In 2019 it received its first investment of €1 million from the City of Utrecht, following which the fund began to fund schemes. A subsequent partnership with the Triodos Bank exponentially increased the capital available. The fund charges a low interest on loans and advises and assists potential recipients to make a case for funding. The initiative combines direct private financing and direct public investment with urban design governance support tools.

- By&Havn is a development and operating company jointly owned by the City of Copenhagen and the Danish state, By&Havn sells building plots to investors and housing cooperatives and actively participates in urban living initiatives from the initial planning phases until neighbourhoods come to life. The revenue from its activities helps to fund major infrastructure projects in Copenhagen including the development of the metro as well as urban spaces, quays, jetties, parks and initiatives in the new urban neighbourhoods. The initiative operates on a commercial basis supported by both direct financing from land value capture and direct public investment, while using support, information, persuasion, and rating design governance tools.

- Concept tendering. Instead of using a direct award or a bidding process (where price is the deciding factor), concept tendering brings to the fore the qualities of place by making them a key decision-making factor equal to or even more important than price. Evaluation matrices are applied to ensure transparency. The concept tendering procedure was first developed in the 1990s in Tübingen, and since then German cities have been able to use a variety of different and diverse criteria, enabling them to compare the quality of submitted projects, some based on complex point matrices and others on unweighted lists of criteria. The mechanism is based on indirect financing combined with incentive and rating tools of urban design governance.

- Oslo waterfront regeneration is a collaboration between Oslo City Council and Bjørvika Utvikling (a joint private / public entity). Quality is secured through a combination of formal and informal tools including a clause in the head agreement which stipulates that each square metre of property sold should yield a defined sum towards the development of public space. A further clause prescribes how finance will be supplied to the project without the municipality taking on any direct financial risk while the coherence of the area is shaped through extensive guidelines and a set of indicators. The regeneration process encompasses a steering mechanism based on the public private partnership and analysis, information, and support urban design governance tools.

A design / finance chicken and egg

A chicken and egg question arose during the analysis of the various cases examined during the research. Does the availability of finance incentivise good design or does the promise of good design incentivise the finance. In most of the cases the two worked together, with a key ambition to create better projects leading to a desire to develop approaches that will deliver on that ambition, approaches with clear finance and design components, albeit at a cost. Such processes, however, require a pre-existing ambition, and this is only likely to come if a pre-existing culture of design quality is first nurtured. Equally, once up and running, the cases explored by Urban Maestro showed that the finance and design sides remain mutually reinforcing, with quality delivered reinforcing the case for and delivery of more finance and more quality.

Of course, financial incentives will be only one of the many incentives created by urban design governance tools. A design competition, for example, may give a very small financial incentive but have a large reputational one with long-term economic consequences for those who take part and are successful. There are also indirect financial impacts from the use of urban design governance tools. For example, a tool that supports the delivery of good design through facilitating the provision of design expertise to either a public authority or development partner, even if it does not give money directly, is de facto a form of financial incentive because the assistance provided translates into lower costs and may (in time) deliver higher revenues from projects. Many of the quality delivery tools, particularly those associated with support and exploration, will have indirect economic consequences.

There are also many real estate actors (public and private) that are already motivated to produce high quality development for combinations of economic, social and environmental reasons. They may not need a financial incentive to do so but engaging with the tools of urban design governance can potentially provide them with means to turn their aspirations into reality, and to inculcate other parties (perhaps public authorities) into that vision. This reflects the notion that much development occurs within a system of networked governance in which motivations are complex and intertwined and will not always be straightforward or always stem from expected sources. In such complex governance environments, Land Value Capture and Public Private Partnerships have particular potential when shaped via urban design governance tools.

Adding ‘design strings’ to the finance of urban development

What was apparent from examining the panorama of practices compiled by Urban Maestro was a strong pre-existing desire to ensure, either that specific developments would be of high quality, or that future (as yet undefined) developments would be. The various financial mechanisms were then used to ensure that ‘quality’ as an objective was written into the operating system that would subsequently deliver those projects. This has a number of powerful effects:

- It ‘locks in’ quality, because in order to access the money and the development opportunity, a high-quality development becomes a pre-requisite

- It sets a high bar early in the development process, ensuring that the decision-making of all actors factors-in clear quality ambitions from the start

- It expands the notion of value beyond a purely economic one to one that might be encompassed in the concept of ‘place value’, namely that projects should maximise economic, social, environmental and health benefits to be considered successful, and that the quality of place is fundamental to this

- It utilises informal urban design governance tools as the means to establish the quality credentials of projects and ensure their subsequent delivery combines these with formal (and sometimes) informal finance mechanisms.

In this way the hypothesis that formal financial and informal urban design governance tools are potentially complimentary was strongly supported by the research. There is no direct financial incentive in the production of a design guide, for example, but the moment public funding is committed or permission to build development is made conditional on meeting its principles, the financial dimension becomes both apparent and powerful. Most of the formal financial tools have an explicit incentive function; in essence they offer funds conditional on specific design attributes being delivered, where the definition of those design attributes are typically established in what the European typology of urban design governance defined as ‘quality culture tools’ before being further defined and applied care of ‘quality delivery tools’. All these tools, with examples, are discussed in some depth in the book Urban Design Governance, Soft Powers and the European Experience.

While combining financial mechanisms with informal urban design governance tools – funding with design strings attached – appears to be very effective at delivering high quality sustainable outcomes, this does not mean that such a linkage is always necessary nor necessary in perpetuity. Because informal tools create a culture within which design is prioritised, over time the need to incentivise design quality through other formal and financial means may fall away, leaving actors that are intrinsically motivated to deliver design quality and who will continue to do so given that the expectation is now established. In such circumstances urban design governance may revert to the use of informal tools in isolation as a means to continue nudging all actors to do even better and to prevent any backsliding if other factors, notably the economic context, changes.

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL