Continuing from the previous blog, and building on extensive evidence brought together in a recently published paper, this blog continues the conceptualisation of design coding. The previous blog identified the value of codes as a distinct urban design governance tool that can establish a ‘wireframe’ of essential urbanistic elements with the potential (although not the inevitability) of optimising place value.

Distinguishing the content of codes from the tool delivering it

Such a wireframe has the potential to contain all the ingredients for what William Whyte characterised as “a social fabric of stifling monotony”, just as it might also contain the ingredients for a sustainable, inclusive and fulfilling place-focused urbanism. But rather than focusing on these larger urbanistic considerations, much attention has instead focused on the association between coding and the neo-traditional outputs of the New Urbanist movement in the USA and places such as Poundbury here. As a consequence, codes have more-often-than-not been associated with the stylistic predilections that often accompany such developments. But, just as the choice of a programming language in computing does not determine the nature of the project being coded, in the built environment it is not the tool that defines the outcomes. Instead, it is the content – the components and parameters – that are loaded into the code.

Speaking from the perspective of a master developer, Graeme Philips has noted “A good code is a filter through which only well-resolved and compliant proposals will pass, but it should also be expressive of the overall design vision”. The vision may be ‘traditional’ in feel (as is often favoured in the USA) or contemporary (as is typical in continental Europe). More significant is likely to be the potential for codes to coordinate site or area-wide strategies that have nothing to do with style: connections and movement, green space and biodiversity, public realm quality, the distribution of uses, variety of building forms and types, walkability and so forth. Ultimately, codes are a designed product and will be value laden just like any strategic planning framework to which they relate, or architectural project that they may help to deliver.

A wireframe used at different scales

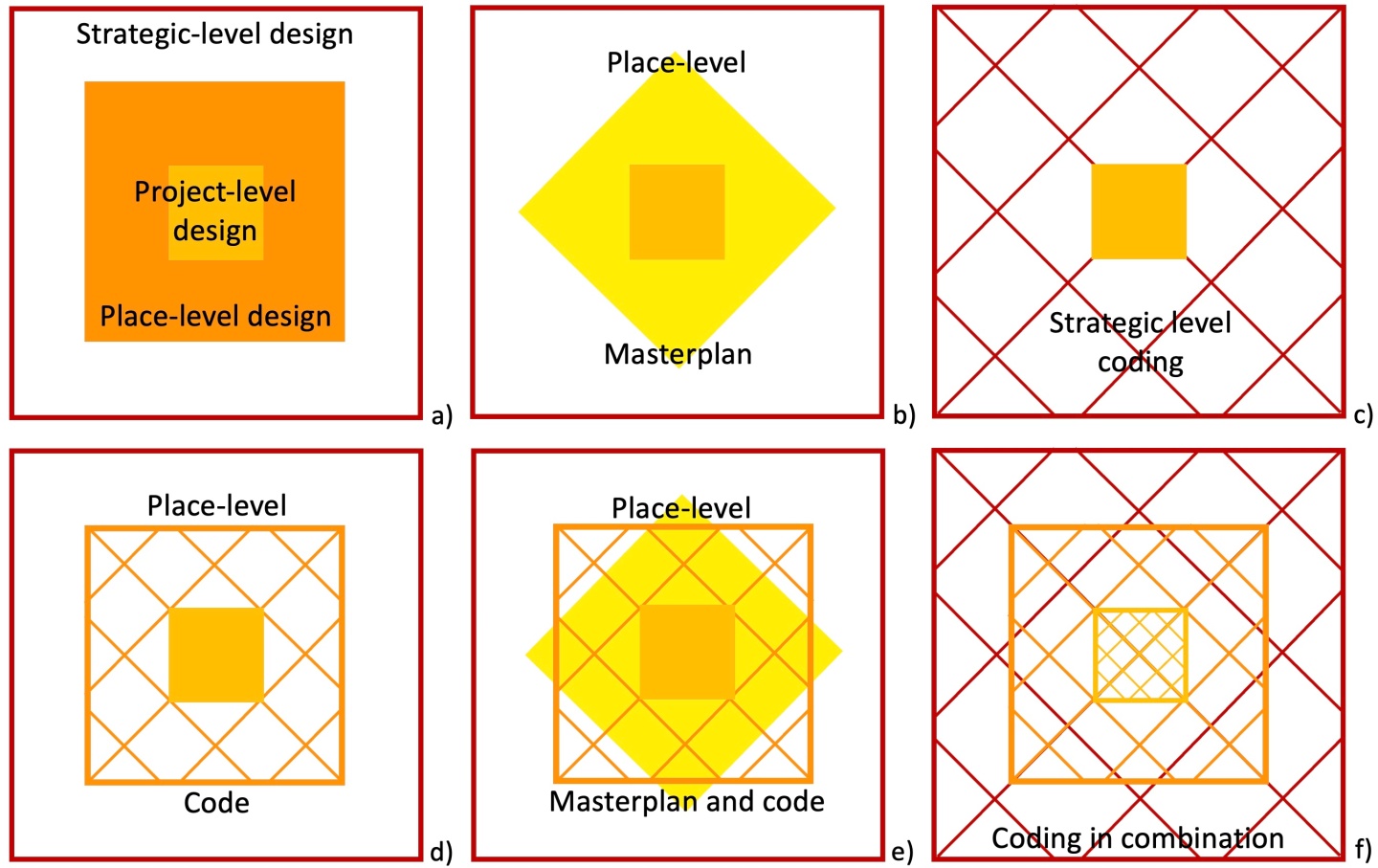

Turning to the scale and sequential implications of coding, here we need to consider three scales (‘a’ in the figure below). At one end of the spectrum, typically some form of spatial planning at a ‘strategic’ scale will determine factors such as the distribution of development, infrastructure, the mix of land uses, and so on. At the other end, individual ‘projects’ are designed in three-dimensional detail and are subject to a range of regulatory processes. While the project scale ultimately defines what is experienced on the ground, project-level design is not necessarily the most important level at which design occurs. By setting the wireframe within which the ‘place’ is defined and matures, the intermediate level place-design has the potential to define the most important relationships in which the greatest public interest resides.

Unfortunately, despite its importance, coherent place-level design is often missing in contemporary development practices because, while place creation is not possible without projects, project creation is possible without place-level design. When it is delivered, typically place and project-level design are given the big bang treatment through a single detailed blueprint masterplan (‘b’ in the figure), although such approaches have been criticised because of the association with what Nick Falk refers to as ‘big architecture’ projects through which designers, incorrectly assume that “if you can visualise everything, you have solved the main problems of development.

Equally, strategic, and place-level design can be unified in a single detailed strategic level tool (or tools) (‘c’), such as a city-wide zoning ordinance. The New York zoning ordinance provides a case-in-point which, a century after its original 35 pages were published, had grown to 900 pages covering a very wide range of detailed coding, nuanced across the city according to local contextual circumstances, and enforced through complex formal regulatory processes. While born of a very different planning system to that in the UK, the approach is akin to practices in England from the 1970s onwards when authority-wide residential design guides and county level highways standards guided much local place-level decision making (not altogether successfully).

In contrast, countries such as Denmark and The Netherlands have long retained a clear distinction between establishing the urbanistic parameters of places (through forms of coding) and that of masterplanning and strategic level design. Codes operating at this mid-level of design (‘d’, ‘e’ and ‘f’) are indirect in their impact, establishing the ‘decision-making environment’ within which others subsequently design final projects. The challenge, in an uncertain development environment or where projects are being built out in phases over long periods of time, is to deliver a more flexible approach that nevertheless has the potential to add both certainly and quality. It is this that the use of place-level codes attempt to achieve either by themselves (‘d’); acting together with a masterplan (‘e’); or used in a staged manner (‘f’). This final use of codes in combination implies the use of place-level codes, either with strategic coding above and / or with project level coding below, the latter for smaller development parcels or at the plot level.

Following the logic path (with flexibility)

This blog post began by comparing coding in the built environment with that used in the field of information technology. While computer software can ultimately be boiled down to a series of 0s and 1s (to binary code) and the fabric of the built environment to solids and voids (figure / ground), coding in both fields is hugely complex in order to accommodate the numerous languages, delivery tools and, of course, objectives – what coding is attempting to achieve. The need is to have a clear vision of what is intended and to write the code in such a way that it will be delivered without fail. Just as a computer must follow its coding – it can’t (yet) decide to simply disregard it if it doesn’t like the direction of travel – so also should a good urban design code lead inevitably and irreducibly to the outcomes defined by and in the code. It should be easier to follow the logic path defined by the code than to ignore it. In the built environment, ideally this should deliver a more desirable set of outcomes than would have been secured without the code, although crude coding can also materially reduce the quality of designed outcomes, delivering the default: unsustainable sprawl.

In England, design codes are being used to deliver a more design focused planning system in the belief that better designed development will be more acceptable to local communities who will thereby be more accepting of new development in their areas. Here design codes are seen as adding greater certainty and reducing the discretion inherent in British planning systems. In countries with a zoning tradition, various forms of coding are being introduced with two purposes. Either to be more responsive to the specificities and nuances of sites – beyond what is possible in a broad-brush zoning system – or to offer greater flexibility to changing market circumstances by coding separately and sequentially for different phases of development – beyond what is possible in a blueprint masterplan. Codes have therefore been linked both to reducing flexibility and to increasing it.

A path towards place-focussed urbanism

With the current drive in England towards the production of authority-wide codes (strategic level coding), there seems to be an alignment with practices in the USA where many form-based codes have been produced as alternatives to, or replacements for, city-wide zoning ordinances. The evidence discussed in the paper on which this blog is based suggests, however, that the real prize remains the production of site-specific design codes (floating-zone codes in the USA) that represent a continuation of the practices that have guided the best development projects in the UK since the 2000s and which are closer in type to the site based regulatory plans found in continental Europe.

Such codes deliver a greater degree of place-specificity that is only possible at a smaller scale involving a design team directly focusing on the site and its potential rather than applying standard types to a remote and abstract site. As I have argued previously, there are many paths to successful coding because codes are not a single tool or process. At the same time, conceptually at least, the ideas (underpinned by practical evidence) in this blog and the last suggest a common framework for the wide range of codes that are currently in use internationally.

As Raymond Unwin noted over a century ago, “communities are seeking to be able to express their needs, their life, and their aspirations in the outward form of their towns, seeking, as it were, freedom to become the artists of their own cities, portraying on a gigantic canvas the expression of their life”. In this sense codes clearly put public authorities (representing those communities) on the front foot, lending them the power to shape a desired outward expression in a proactive and positive manner through a robust and holistic wireframe for a place-focused urbanism.

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL