In the previous blog I explored the crisis on our high streets driven by the move to shopping online and proposed a new sun model for thinking about shopping choices. I concluded that faced with the challenges, the UK Government is adopting a rather confused combination of deregulation and intervention to address the problem. Let’s pick up where the last blog left off.

De-regulation – Ad-hoc renewal

The first approach is reflected in the de-regulatory predilections of Government as encapsulated in the increasing use of permitted development rights (PDR) – by-passing the need for planning permission – to deliver more housing. Undaunted by reports of the poor quality of accommodation being delivered in this way, further liberalisations in March 2021 were justified almost entirely on the need to tackle the crisis on England’s high streets. The changes gave PDR rights to a new mega-class (Class E) allowing the conversion of all commercial, business and service uses to residential.

The Government argued that allowing more housing in such locations will diversify uses and help to support retail through having larger populations within walking distance. A side effect, however, is the removal of almost the only (albeit crude) mechanism, short of public sector ownership, for local authorities to ‘direct’ an appropriate mix of uses on high streets. A key danger, therefore, is that deregulation might reduce the very diversity that it seeks to inject. Given the choice between the uncertainties of a retail industry in crisis, an office market also in transition (as white-collar workers increasingly choose to work from home), and the low values associated with small scale manufacturing and community functions, the logical approach for investors will be to run to residential, leaving a ‘gap-toothed’ appearance on affected streets.

Intervention, as the alternative to deregulation, is far more complex, cutting across the realms of planning, design and curation.

Intervention – shaping through proactive planning

In contrast to its deregulatory instincts, the UK government, with increasing urgency has also encouraged a more active approach to the nation’s high streets, moving from a small £1.2 million fund in 2011 to implement ‘Portas pilot’ schemes up to a £1 billion fund in 2019. The step-change in resourcing has not, unfortunately, been followed by a step-change in vision, with funding tending to focus on limited one-off capital projects, rather than on the fundamental re-thinking of high streets called for by some commentators.

Retail executive, Bill Grimsey, for example, argued that every town centre should have a dedicated plan. In this the core retail area should be defined and protected whilst retail in secondary areas should be allowed to shrink through a combination of conversion to residential uses and the active relocation of valued local retailers. Research for the Greater London Authority notes that planned shrinkage can encourage an intensification in the frontage that remains – including by building residential over and behind retail – avoiding the problem of permanent holes appearing in frontages.

Such a strategy relies on regulation, alongside more proactive planning, public / private partnership and potentially land and property assembly and development. It would benefit from the already well-established trend of a growing population living within walking distance of high streets, a population that has been increasing at double the rate of other locations.

Intervention – shaping through proactive design

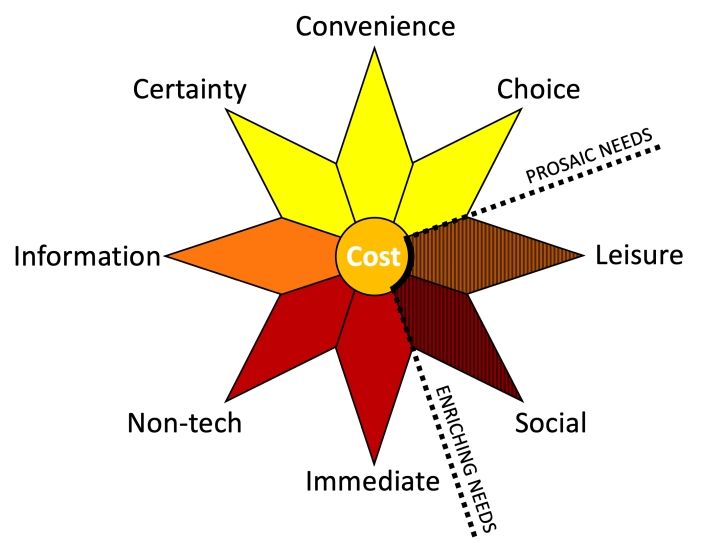

Jan Gehl famously distinguished between necessary, optional and social activities in the use of public space, reflecting the idea that for people to really engage in places they need to want to do so because the place is appropriately conducive. The sun model discussed in the previous blog can be interpreted in a similar way, with the more prosaic factors associated with shopping set against a smaller number of enriching factors related to the very human desire to be together and enjoy ourselves.

My own pre-pandemic research confirmed a strong association between these enriching needs and the quality of streets. By comparing high streets that had been subject to significant public realm re-design and investment to those that had not, the work identified that improvements to the quality of the street fabric encouraged people to walk more, to stay longer and ultimately boosted the desirability of surrounding retail space and reduced vacancy.

UK Government funding for emergency design interventions in the country’s high streets in the wake of the covid pandemic envisaged similar possibilities. As an unpublished letter from the Department for Transport to local authority Chief Executives argued: “We have a window of opportunity to act now to embed walking and cycling as part of new long-term commuting habits and reap the associated health, air quality and congestion benefits”. Resulting changes have sometimes been temporary and sometimes permanent, but in focusing on a “new era of walking and cycling” have driven changes nationally with a proven track record of boosting spend in shops.

Intervention – shaping through proactive curation

It has been widely argued that, in order to survive, the high street will need to find new purpose in becoming the latest arena for customer experience innovation. Extrapolating to the larger scale, the street itself now also needs to be part of that positive experience. This represents a major challenge for traditional shopping when the competition – internet platforms, shopping malls and even out-of-town retail parks – are highly curated in order to optimise the experience in terms of its convenience, the choice on offer, and the experience of navigating those choices.

Managers of large shopping malls, for example, have long understood the value of mixing retail, entertainment, event spaces, and restaurants in order to keep users coming back and to encourage movement in a manner that optimises spend. The thought of giving up control on the mix and incorporating non-active uses into it as suggested by the de-regulatory (PDR) changes impacting on English high streets would be an anathema. Town Centre Management, in various guises, and Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) have developed in an attempt to transfer private sector methods to publicly managed streets, but the reality of fragmented ownerships, limited resources and a lack of focus in the public sector on the growing threats to traditional high streets have combined to limit their impact.

While the public sector, typically, has direct control of only a limited stock of buildings in most town centres, it does have control over the key public services – with the potential to re-locate them back onto high streets – and of the public realm. Local authorities can (along with private partners) deploy temporary uses in the public realm in order to curate the experience, ranging from fun activities (e.g. events, fairs and demonstrations) to retail opportunities (e.g. farmers markets), to works of art and performance. More proactive English local authorities are also stepping in to pick up cheap retail assets in order to repurpose them to better serve local needs. More radically still, models such as Town Centre Investment Zones (TCIZs) seek to pool ownerships and responsibility in a single investment vehicle focussed on collectively curating entire streets.

Together, the range of different approaches can be represented on a ladder that moves from passive approaches to curating retail environments (the normal approach in England) to more active ones, and to total control models. The challenge is now to move up the ladder!

A place attraction paradigm to conclude

In the longer paper from which this discussion is drawn I argue that traditional shopping streets face an existential crisis, and how they react will determine whether they have a long-term future or are doomed to inevitable decline. Drawing from the analysis, it is possible to conclude that governments, local governments and those with management responsibilities for high streets need to systematically consider their response to the four critical place-based shopping choice factors contained in the sun model.

Setting these against the three proactive intervention factors begins to answer the question previously posed concerning what are the key place-based factors that will help to guarantee a future for traditional shopping streets.

In doing so I conclude that if we wish to avoid the sun setting further on these valued places and the rich ecologies of functions they host, then the answer can only be found in more and better public sector intervention, not less, working in partnership with private actors. What is clear is that we have moved beyond the old movement economy and centrality paradigm where just to be in the right place was enough because people would come, to a paradigm in which place quality is all. High streets which prioritise proactive intervention in order to address the place-based factors that make people actively wish to visit will survive and thrive. Those that don’t will surely decline and die.

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL

February 2022